For millennia, the inhabitants of the Scottish Outer Hebridean islands have been building with stone, leaving their history preserved in rock.

TEXT STELLA MARTIN PHOTOS CHARLES TAIT

There is an entrance hole. In the middle of an enormous mound of stones, there is a passage leading inside. I can’t resist it and wriggle my way in, on hands and knees. After a metre or two, the passage opens up and I switch on my torch.

To my side, large flat stones have been wedged upright. Perched on these, more massive, flat stones form the ceiling of the chamber. These, in turn, support the massive pile of stones which makes up the cairn. Their weight must amount to tonnes, but I don’t get too nervous – this structure has been here for about 5,000 years. It’s not going to collapse now.

Outside, I clamber over heather and boggy peat, as I work my way around the cairn. Twenty-four metres in diameter, it is almost five metres in height. Cremated human bone, Neolithic pottery and carved flints found inside suggest it was used for Stone Age burials.

The Bharpa Langass cairn is the best preserved of numerous chambered cairns found throughout the Outer Hebrides, off the north-west coast of Scotland. Although visible from the roadside, it is not much visited. That is one of the wonderful aspects of these islands – ancient remains of human endeavour are mainly unfenced and unguarded, left as they always have been, open to the weather and the curious passerby.

Langass is on North Uist, one of the largest in a chain of over 200 islands which make up the Outer Hebrides. Life is not easy. Many of the smaller islands are now uninhabited and populations are dwindling as young people move away.

When the first hunter-gatherers arrived, following the retreat of the ice at the end of the last ice age, the climate may well have been kinder than now. In Lewis, the northernmost island, there is evidence that barley and other crops were grown where now there are only peat bogs.

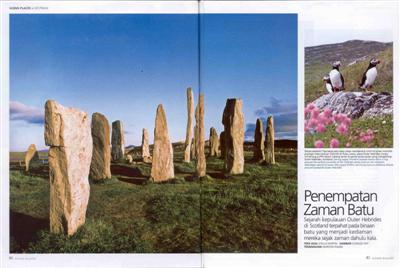

It was at this time that the great stones of Callanish were erected. I stand in awe. Thirteen massive stones form a circle around a central monolith, 4.7m tall. Another 33 stones form rows, leading up to the circle. Near the centre are the remains of another chambered cairn. They were erected perhaps 5,000 years ago.

The standing stones of Callanish are like a northern Stonehenge. But they are older - and there are no ticket booths, turnstiles or hordes of tourists. We simply let ourselves through the gate and wander around and through the stones.

The rock used – Lewissian gneiss – is not only one of the most ancient in the world, but also very beautiful with swirling patterns of grey. In the lee of the central monolith we shelter from the wind along with the three other visitors, all strangers to each other.

Perhaps an hour passes as we discuss everything from wind power and climate change to the Gaelic language (spoken by the locals) and literature and I realise that the circle must always have been a social centre, a place for a good chat. Then our newfound friends drift away and we have the stones to ourselves. There is no closing time and it is hard to leave. We stay for two hours.

Our encounters with the rocks of Lewis are far from over. Just a few miles to the north, as the grouse flies, lie the remains of Dun Carloway, an Iron Age broch dating back about 3,000 years.

Duns, or brochs, were massive stone-built houses and their remains are to be found throughout the islands. Two concentric walls, 3m thick, were linked with massive flat stone lintels.

The remains of the walls at Dun Carloway are still 9m high and we are able to climb the staircase, within the walls, which would once have been used to reach galleries at higher levels. It is simply astonishing that these walls, constructed without mortar, are still standing 3,000 years after they were built.

Just a few miles further and we jump ahead to the time of the Norsemen. The first Vikings may have arrived here one and a half thousand years ago, making the Hebrides one of their main bases. Many of the place names are Norse and many of today’s Hebrideans probably have Viking ancestors. Here, at Shawbost, a Norse mill and kiln have been restored.

Architectural styles evolved slowly in the Hebrides. The basic plan of the broch, seen again in the Norse mill, was used in the building of number 42 Arnol in 1885. Known as a blackhouse, it is a typical Hebridean dwelling of recent times and was inhabited until 1964.

Since then, this house has been restored and opened to visitors. A small peat fire is burning in the middle of the main room. Traditionally, never allowed to go out, the fire serves still to keep the thatch dry and functioning.

The absence of trees throughout the Hebrides made roofing difficult. Drift wood and even whale bones were used to support a layer of heather turf, covered with straw thatch.

But the creation of walls was never a problem. Whatever else is lacking in the Hebrides, there is plenty of rock in this hard place.

OUTER HEBRIDES FAST FACTS

Population 26,370

Language English and Scottish Gaelic which is widely spoken as the first language

Currency Pound Sterling

Religion Christianity – predominantly Catholic in the southern islands and Protestant in the north.

Climate The climate is remarkably mild considering its northerly position. April to September are the driest and sunniest months with long days and just a few hours of darkness. The average mean maximum temperature for August is 16ºC. Winter months are wetter and cooler and the days short.

Malaysia Airlines flies to London twice daily with code share links to Glasgow

Getting there

Regular vehicle and passenger ferries link the Outer Hebrides to the Scottish mainland at Oban and Ullapool, and to Uig in Skye. Inter-island ferries link Barra to Uist to Harris. Contact Caledonian MacBrayne for details and bookings; Tel: +44 (0)8000 66 5000; fax: +44 (0)1475 635235; e-mail: reservations@calmac.co.uk; web: www.calmac.co.uk. Check out their special ‘Island Rover’ and ‘Island Hopscotch’ deals and be prepared to book between April and October, particularly in July and August.

Oban is 90 miles/145km from Glasgow. The drive takes about two and half hours.

© S.B. Martin. All rights reserved

|